I was raised by a mom diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Back then, in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, not even the so-called Ph.D’d professionals knew what was going on or how to deal with “crazy.” And if they didn’t know, we – my immigrant English second language family – couldn’t possibly have known. It’s part of why mamma went without any kind of treatment, hearing voices and seeing things that really weren’t there, for far too long, making her a danger to herself and to us.

I was raised by a mom diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Back then, in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, not even the so-called Ph.D’d professionals knew what was going on or how to deal with “crazy.” And if they didn’t know, we – my immigrant English second language family – couldn’t possibly have known. It’s part of why mamma went without any kind of treatment, hearing voices and seeing things that really weren’t there, for far too long, making her a danger to herself and to us.

I still can’t shake memories of a 14-year old me in 1979 helping my papà commit mamma to a hospital psych ward. Part of me exhaled in relief, knowing we were rid of her, even if only for a little while. Another part of me became consumed with guilt over what I then didn’t fully understand had to be done.

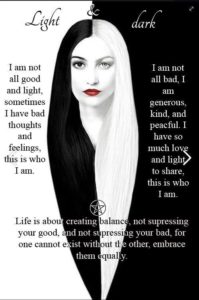

For much of my life, I tried to separate my parts, doing my best to distance those genes of insanity that I had inherited through no fault of my own. I kept my mamma at arms-length, afraid of the demons she battled and the parts of her she could not control. And I kept our family’s schizophrenia a secret from the outside world, lest I be subjected to the stigma and discrimination by association.

In my own 20s, part of me feared if somewhere, in some other part of me, there lurked the voices, the hallucinations, the paranoia, the legacy… I remember being mesmerized by the TV news at the unfolding of a woman named Laurie Dann who had just shot six children in a nearby elementary school. The stand-off with police would end with her committing suicide. Those interviewed detailed a long history of societal withdrawal, erratic behavior and psychological intervention, but no one could have predicted the tragedy. Back then in 1988, the incident was considered a rarity.

It did spark debate over gun control and about committing people with mental illnesses who were incapable of making informed decisions about their own care to health facilities against their will. People blamed family, friends, and authorities for not doing more sooner.

I kept silent, but couldn’t help the involuntary nodding of my head. I understood what most could not. “There but for the grace of God go I.” Because only those of us who have walked in these shoes – those intimately connected with mental illness – are able to understand its reality.

I couldn’t wait to turn 30, believing that exiting the second decade of my life and entering into the third would magically make mental illness pass me by.

It did.

But not before taking root in my little sister, two years my junior. The baby of our family was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia at the age of 24. And so, a dozen years after having committed mamma, little had changed, as I found myself in a weird déjà vu, repeating the process, with my own trembling hand signing her commitment papers to a psych ward.

When I was a child, my Mamma’s voices told her to kill her children. Somehow, she fought them off. We had several guns in the house. She kept some under her bed, constant threats that kept us up at night.

My sister’s voices had convinced her that she had written the Holy Bible and was a multi-millionaire thanks to a drug she invented that wiped away all disease. I wish. She would die much too young at age 42. Shut away in a senior center that due to financial need doubled as a mental-health assisted living center, my sister rotted away.

Throughout it all, we did the best we could with what we had and what we knew to do. That said, no matter how much we researched and sacrificed and sought help, it never was enough. Never were we at peace with any kind of guarantee at an outcome that didn’t include tragedy.

As much as part of me has rejoiced in having escaped insanity within my own self, another part of me knows that I did not, and I never will. Because every time someone who hasn’t a clue what life is like living with and/or loving someone with a mental illness wags a finger and raises their very uneducated voice of what should have been seen or known or done, or how getting rid of guns alone “IS” the answer, I am reminded of the true definition of insanity.

With ever-increasing frequency, unstable people make judgement calls. Some are in positions of power. Others haven’t yet earned their high school diplomas. Some lobby with conflicts of interest. Others battle bullies on the playground. Some have their finger on a call button for nuclear war. Others have easy access to automatic weapons.

“Crazy” comes calling in many forms again and again. There are, indeed, “red flags” that go unnoticed and unreported, in great part because we can no longer distinguish between “normal” and “nuts.” And even if we have the courage and the stamina to raise our voices or navigate any attempt at getting help, there’s actually very little real help to be had, thanks to misunderstandings, disappearing programs and support services, and the ever-dwindling lack of government funding in exchange for judgement and prayers.

Social commentary should include a snapshot of the millions of homes wherein madness resides along with mainstream normalcy. It shouldn’t just be a conversation when a shooter goes on a deadly rampage or an authority figure takes to Twitter. It shouldn’t be an isolated topic of conversation. It should be part of the whole, a bigger discussion that stops fanning flames of “other than me” enemies and stops funding for more war, more walls, and more wealth.

The true enemy is within. We all are part of the problem. Just as we all are part of the solution.

Leave a Reply